Consumer behavior is changeable, difficult to predict, and subject to rapid change. So to get an accurate handle on what’s blowing in the change-winds generated by megatrends relevant to the automotive world, we’ve asked in an expert: Jimena Martinez, a qualified psychologist and interior designer whose expertise and experience, combined with her knowledge in automotive and connected goods, enables her to deliver dependable insight into contemporary consumer needs and wants. Martinez is co-founder of LemonLab, a qualitative research agency providing consumer insights in fields ranging from luxury to automotive to consumer goods.

We interviewed Martinez on consumer views of car interiors, with particular attention to the sustainability aspects impacting the future of car interior design.

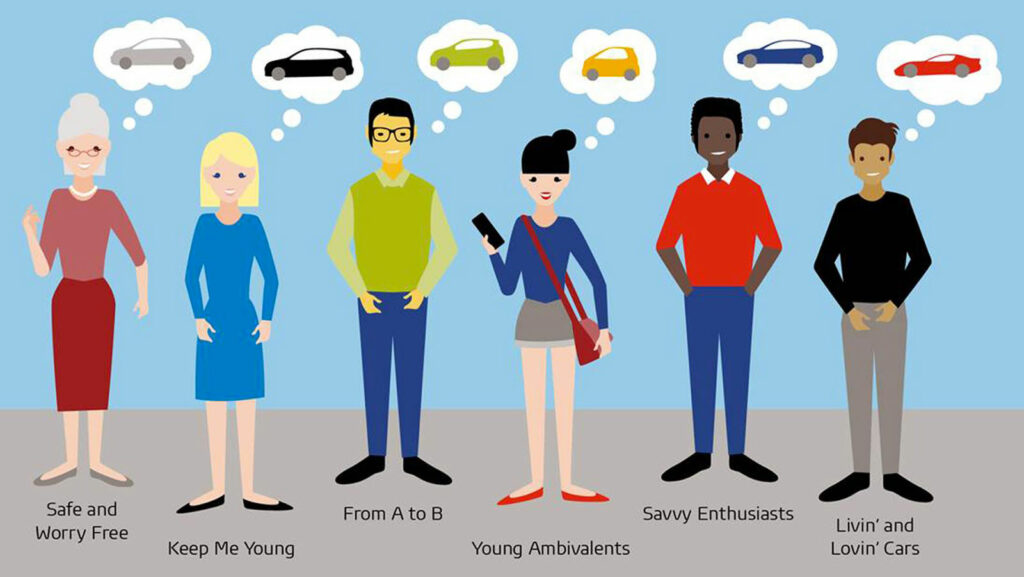

Decades of research and countless publications dedicated to consumer behavior have validated ideas and inspired innovation processes. However, they have also revealed a fundamental truth: there’s no singular entity that can be defined as ‘people’. Even if we generalize, it’s evident that people don’t truly know what they want.

Freedom and Sustainability

Cars have been a part of our lives for over a century, fulfilling roles far beyond transport. They’re symbols of aspiration and desire, status symbols, adventure companions. Today, cars sit at the heart of humanity’s most pressing concern: how to live sustainably while still enjoying freedom and spontaneity.

When trying to understand what consumers would like in car interiors, the real task is deciphering how their contexts, lifestyles, and social environments shape their decision-making processes. It’s about examining how their conscious and subconscious minds interpret the current landscape—the zeitgeist—and ultimately arrive at a choice, even if that choice is to delay a decision until things feel more certain.

Sustainability as a perceived duty

Consumers today feel overwhelmed by the endless and complicated discussion surrounding sustainability and environmental compatibility of everyday activities and items. They are unsure about what constitutes a good choice. Overall, they don’t have the answer. Sustainability isn’t experienced as a need or a desire, but a sense of duty—a form of consciousness and engagement. This engagement is no longer celebrated as an added value or perq; consumers expect large, big-money industries to deliver eco-compatible, sustainable products made in eco-compatible, sustainable ways. In uncertain economic times, they need brands to shoulder the burden of responsibility by providing solutions that free them from worrying about sustainability.

Consumers expect automakers to handle sustainability, but they won’t tolerate greenwashing or misleading claims. They are demanding, increasingly skeptical, and, in many cases, skeptical or even cynical. Every advance in sustainable discussions often leaves them feeling more like victims than participants—caught in a cycle of guilt, blame, restrictions, and politicized distortion of science.

More than ever, consumers need liberation from the mental load of sustainability. In their daily lives, they already deal with separating recycling, purchasing eco-friendly products, and limiting consumption, travel, and driving. The connection to the goods and services that once inspired them has eroded. Here lies the challenge—and the opportunity. Cars are more than objects; they have the potential to become enablers of experiences, spaces for living, sharing, and exploring. Once a car becomes a financial burden, a short-term compromise, or a mere functional object, sustainability alone won’t naturally rise to the top of their purchasing criteria. Sustainability needs to come paired with economic benefits or surprise-and-delight features.

Electrification Doesn’t Solve Everything!

What consumers expect from automakers today isn’t just a list of sustainable features. They’re after a redefinition of the car itself. They want a new vision and relationship with the vehicle that goes beyond just ‘it’s electric, so you’re sustainable’. In the medium- to long term, EVs will become the norm, and simply being electric won’t be enough to satisfy the idea of a sustainable consumer. The time of the militant, green-driving idealist has passed. Such engagement is now seen as costly, shortsighted, and riddled with compromises. When the fundamental benefits of driving are challenged by range limitations, insufficient charging infrastructure, and increasing restrictions, consumers won’t settle.

Automakers need to remember that driving speaks to three fundamental human needs: safety, connection, and freedom. This is why consumer insights—not just consumer research—are crucial. Consumers seek a balance between pragmatic and emotional triggers. Meeting basic expectations for sustainability in car interiors might check all the functional boxes, but it won’t spark emotional connection or excitement—not even for the most pragmatic buyers.

Sustainability: Beyond ‘Must-Have’

As society evolves, so do consumer needs, driven by innovation. For a time, electric driving was synonymous with luxury, offering silent power and advanced technology accessible to the happy few. Yet even premium EV brands with marketing centered around sustainability and simplicity struggles to meet certain emotional needs. While the technology is impressive, it lacks long-term engagement, personalization, and consumer-focused UX. Similarly, when it comes to sustainable car interiors, consumers might not know exactly what they want, but they need to feel heard. They want industry to interpret their unspoken wishes and deliver user experiences that go far beyond the must-have features of a sustainable interior.

Full sustainability as a standalone benefit isn’t enough, just as technology alone isn’t, either. For most consumers, outside of niche enthusiasts or those with high budgets, the decision to pay extra for an ecologically-sound interior hinges on added emotional or functional benefits, which sustainability alone doesn’t provide. Consumers might be willing to spend more on interiors offering tangible health or comfort benefits, such as improved air quality or luxurious textures that create a sense of coziness and indulgence. They may also appreciate proven long-term economic advantages tied to sustainable materials or processes. In these cases, sustainability becomes part of the actual value rather than just an abstract concept.

Consumer clinics, a cornerstone of traditional research, remain useful for validating concepts. However, they must be interpreted with caution. The insights they provide are often snapshots of a moment. Using this data to design cars that will hit the market four to five years later requires careful extrapolation to anticipate future scenarios.

Without considering the broader cultural and social dimensions of consumers’ lives, the results risk being overly neutral, resulting in designs that appeal to no one. Similarly, designing a sustainable car interior must go beyond the idea of completely-green brands, which often end up as niche players, appealing only to a small, militant audience. A car that feels overly green—natural and sustainable but lacking aesthetic appeal—might elicit polite admiration, but rarely a purchase.

Brands that deliver authentic sustainability while tapping into emotional connection will engage consumers far more effectively than brands relying solely on their eco-credentials.

There isn’t a straightforward yes/no answer to the demand for sustainable interiors. The art of design thinking lies in creating scenarios that integrate as many variables as possible, addressing consumers’ practical and emotional needs in their socio-cultural contexts. When done successfully, these scenarios establish connections that resonate deeply and make complete sense, delivering products that consumers don’t just accept but truly desire.

Data-Informed Design

As an integration to qualitative insights, universities like the Hochschule Niederrhein in Germany and the Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden (whose studies are summarized in this article) are also working on qualitative and quantitative data to understand how the uncertainty regarding customer expectations for a sustainable car interior design can be reduced.

The information gathered through qualitative and quantitative research methodology by researchers of these two universities is the result of investigations of customer perception and wishes regarding sustainability in electric cars. These data are then used as input for a sustainability-driven, data-informed design process.

The objective of data-informed design (DID) is to drive decisions in the design and development of products, services, and systems through a thorough understanding of available data. DID can help within a design-for-sustainability framework to identify patterns and trends as well as to make predictions about future trends. This can help designers and engineers to create products that are better aligned with the needs and wants of their customers. The data can also be used to test and validate design decisions, providing a more objective basis for making design choices at very early stages of product development.

While data can inform design decisions, it should not dictate them. Designers must use their expertise and intuition to find creative solutions that align with the project goals while using data as a tool to inform and support those decisions.

Decline of the Car as a Status Symbol

There is an ongoing decline of the car as a status symbol. Owning a car is becoming less important, particularly among younger generations, who no longer see the car as a symbol of status but rather as a functional tool. This shift in mindset is leading to increased interest in shared mobility and car share services, as reflected in research like the 2015 Ford Automotive Zeitgeist Study, wherein a significant portion of respondents expressed interest in using environmentally friendly vehicles and shared cars for ecological reasons.

As the importance of engine performance, exterior design, and vehicle propulsion diminishes with the rise of electric vehicles, the focus is shifting towards the interior experience. The demand for durable, adaptable, and aesthetically appealing vehicle interiors is growing, especially in the context of shared mobility. Consumers expect manufacturers to adapt and meet these ecological demands, contributing to decarbonization goals. Driving and interior experience are becoming more relevant to customers, offering the potential for manufacturers to differentiate and remain competitive.

Researchers have been concentrating their apposite investigations on how potential customers perceive the sustainable interior of an electric car, and whether the design of new materials for car interiors needs to differ from traditional materials to meet evolving customer preferences for sustainability, durability, and functionality.

Key Findings

- The interior plays a major role in the sustainability assessment of a car.In general, sustainable materials are perceived as future-oriented, but they should be indistinguishable, design-wise, from conventional materials.

- These materials should be of at least the same quality—durability, wear resistance, etc—as common materials.

- Visually, a classic and simple interior design is preferred.

- Natural tones are less demanded in the interior.

- Materials play an essential role. Sustainable design should use sustainable and pollutant-free raw materials, recycled materials, and resource-saving production.

- No plastics, but natural fibers. Start with seat covers, carpets, and roof linings

Data-informed design strikes a balance between using data to inform design decisions and allowing designers to use their expertise and intuition to create meaningful and engaging products. From these results, we can gather that the DID process is not in conflict with scenarios identified by consumer insights, but can complement the qualitative view introducing more objectivity into the design decision-making process and allowing design management to make more informed and strategic decisions.